editorial" "

Some politicians have already been raised ” “"to the honours of the altars" in Europe; for others the processes of beatification ” “have been opened. Can politics lead to sainthood?” “” “

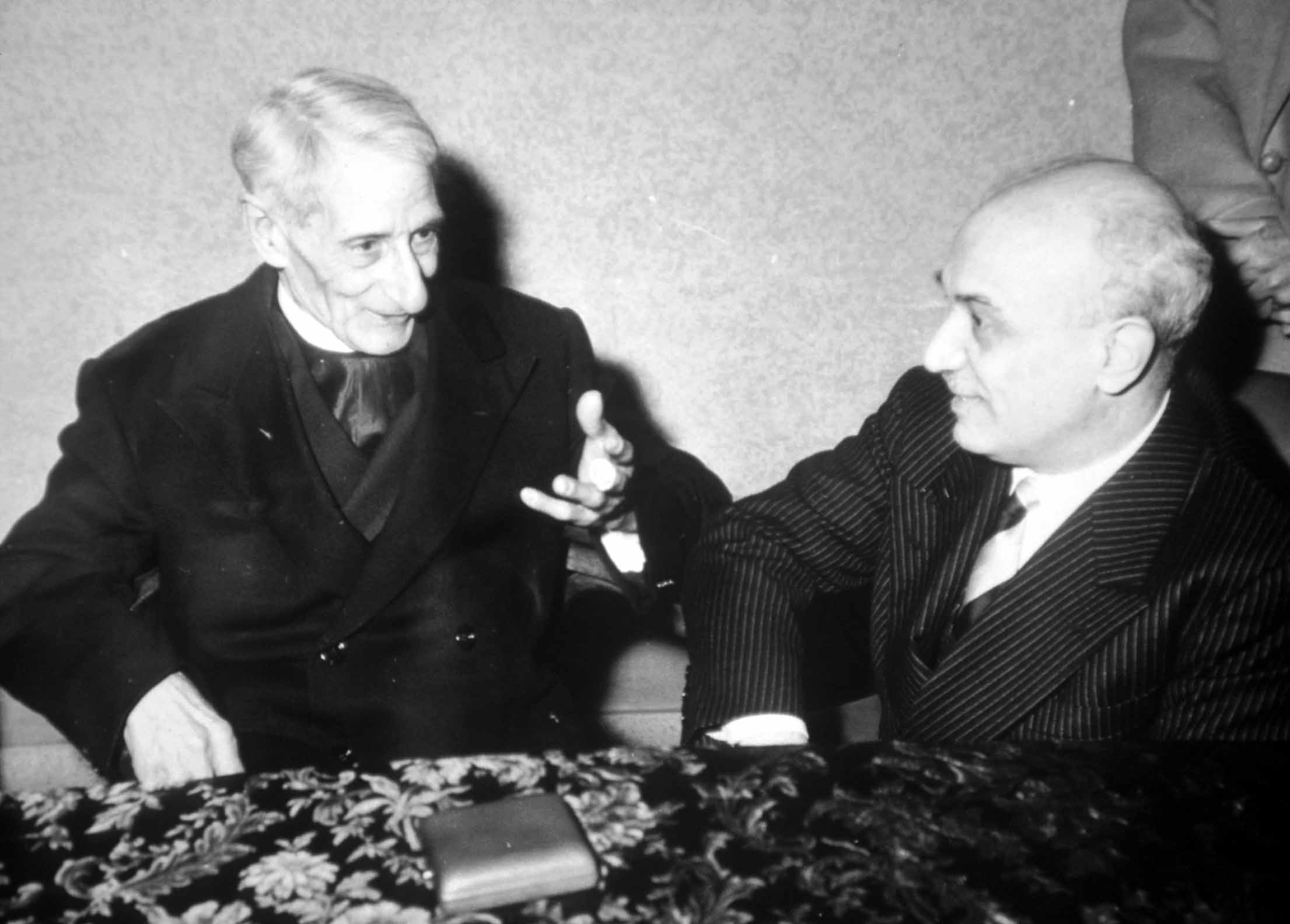

The recent opening of the cause of beatification of don Luigi Sturzo prompts a question: can political commitment be a way to sainthood? In our time of the crisis – moral, spiritual, social – of democracy, the question may seem paradoxical, if not downright provocative. The community of saints consists of kings, of soldiers, of shepherds, of peasants, of sick men, of the rich and the poor, of intellectuals, of mothers of families. They are a very mixed bunch, whose configuration has changed in the course of the centuries to adjust to the needs of the Church and the expectations of society: “We want to discover in saints what unites them with us”, said Paul VI. When the Church prepares the beatification of politicians, she seems to favour the holiness of the action based on the harmony between interior and exterior life. In the past sovereigns have been beatified or canonized, but never politicians in the modern sense of the word. The great Tudor statesman Thomas More (1478-1535) may represent, in terms of his sense of sacrifice, the very type of the man of Christian government, and indeed he was proclaimed patron of politicians during the Great Jubilee of the year 2000. But, to tell the truth, he was canonized, not so much for his action of government, as for his martyrdom, for the fact that he chose fidelity to the Church of Rome rather than to his King. Closer to our reflection would seem to be Nicolas of Flüe (1417-1487), the founder of modern Switzerland who, after an intensive political career, withdrew to solitude and prayer. Nonetheless, in contemporary Catholicism political action was long considered a somewhat improper activity, in the framework of democracy, whose parliamentary structures encourage compromise. In the nineteenth century, the privileged field of Catholic commitment, that led at times to the recognition of saintliness, was that of social action. With Pope Leo XIII, democracy was defined as an acceptable regime; Pius XI defined politics as an action of charity; and Pius XII in 1942-1944 presented the democratic regime as the political system that best permitted the realization of gospel principles. This attitude to politics was encouraged by Vatican Council II (the Constitution Gaudium et Spes). The Apostolic Exhortation Christifideles laici (December 1988) on the vocation of the laity in the Church and in the world, defined holiness as the perfection of charity in ordinary, family, professional, social and political life. This theological and spiritual climate encouraged the question of the beatification of politicians chosen to give a sense, or provide a model, to the action of Christians engaged in the res pubblica. Some processes had already been opened, even before that of the founder of the Italian People’s Party: in Italy, Alcide De Gasperi, founder of the Christian Democrats, and head of the Italian government from 1946 to 1953; Giuseppe Lazzati, director of Catholic Action, founder of a secular institute and rector of the Catholic University of Milan; Giorgio La Pira, the “saintly mayor” of Florence; Igino Giordani, he too elected to the Parliament that drafted Italy’s Constitution and with Chiara Lubich among the founders of the Focolarini; in France, the processes of Edmond Michelet and Robert Schuman have been opened. To raise a politician to the honours of the altars may be surprising and risky. Is there not a risk of beatifying his party? Are these processes opened too soon? Does not political action imply virtues that are not those of charity, but of calculation, ‘reason of state’, cynicism? Are politics, the art of the possible, compatible with the absolute virtues of sainthood? In truth, the possible beatification of politicians has the merit of showing that even today it is possible to conduct politics in another way and remain faithful to one’s own faith in action, and that political commitment too can respond to noble aspirations. Defending and illustrating the genius of Christianity, showing that this is necessary for reinventing democracy and service to the community, that politics is a form of holiness, as St.Thomas said, this, it may be said, is the sense of beatifying a politician engaged in modern democracy.