Regional elections

Success of the extreme right. Gaullists and Socialists rank behind. The merits of the nationalistic leader and the opponents’ mistakes. While waiting for the outcomes of the second ballot of December 13, Europe takes stock of widespread political movements sprung at the grassroots, alien to traditional political parties and frequently eurosceptic.

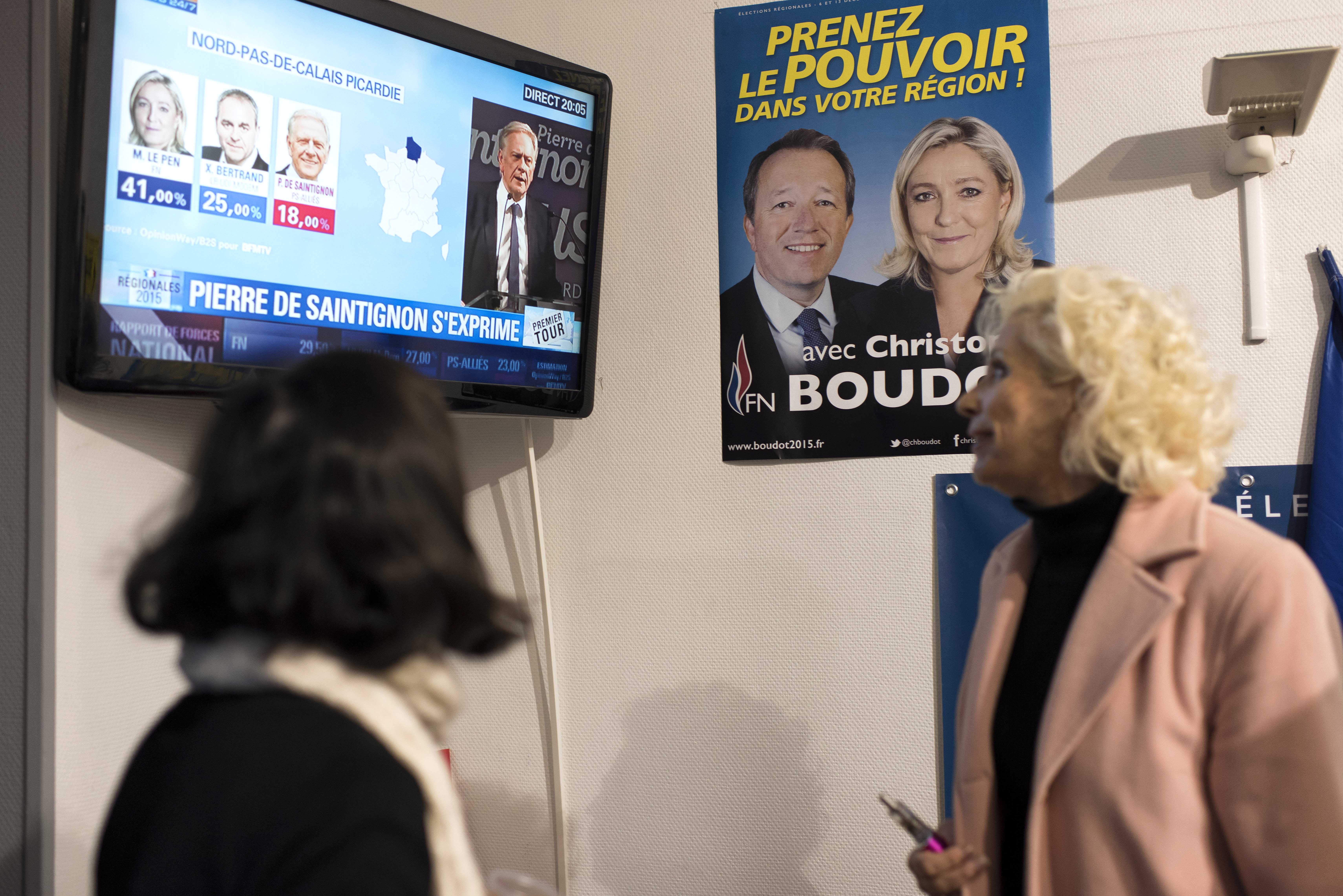

The attacks and 130 dead in Paris; the high numbers of foreigners; unemployment and economic stagnation; suburbs neglected and disadvantaged coupled by a faint international role, despite the air raids in Syria. These are just some of France’s peculiar traits, called to the polls past Sunday, December 6, for the regional election. Indeed, these features underpin the unquestionable success of the National Front in the first round of elections, with the party led by Marine Le Pen at 28%, in pole position for a runoff next Sunday in 6 of the 13 regions of the country, followed by the Gaullist centre-right of Nicolas Sarkozy, with 27% , and by the Socialists of President François Hollande (23%).

From regional success to the Elysée? The second round of 13 December could downsize the National Front through a withdrawal of the Gaullists or the Socialists, as was the case in the run-off between Chirac and Jean-Marie Le Pen, in the presidential election of 2002.

In this case a good electoral system and a solid Republican architrave could cushion the blows of Lepenist populism.

Indeed, FN’s success cannot be played down as political folklore or “emotional vote”: if six million citizens of a democratic State respectful of civil liberties decide to cast their vote to FN the reasons must be sought elsewhere, in order to understand today’s France and today’s Europe. In fact, Marine Le Pen is a clever politician, concrete and with much political experience. She renewed the face of a party that had given way to racism; she renewed its old-dated demagogic legacy; she held high the banner of nationalism, (an-ever winning claim in France) being overtly anti-Europeanist at a time when Europe was in deep waters. Today FN is supported in the north (Calais) in the south ((French Riviera, Pyrenees), in towns and villages alike. The party has opened up to candidates with a potential electoral return, including Le Pen’s young niece Marion. Marine Le Pen thus can tell the French people they can trust the Front National, entrusting her the leadership of regional governments and perhaps, in the near future, even the presidency.

Merits and demerits. However, FN’s results should be ascribed not only to the merits of Madame Le Pen, but also to the demerits of the Republican right and of the Socialist and green left. These two political factions are still divided internally (two minor parties, one to the right and the other to the “green” left, respectively gained 3% of all votes), they have lost political consensus over the past years, lacking specific political identity. Sarkozy blamed Hollande and the Socialists, overlooking the fact that he had lost the credibility and the support of the French people, to the extent of favouring the victory of Hollande in 2012. Moreover, the president-in-office has had to govern a Country at the peak of its economic downturn and terrorist threats, with the twofold blow against Charlie Hebdo and the Bataclan Concert Hall, the refugee-crisis and the ISIS factor.

Widespread populism. The outcome of the French election was interpreted with excessively catastrophic tones by the media. The votes gained by Le Pen in France’s regional election are equal to, if not less, the votes gained by other so-called “populist” movements in European Countries. Just consider the United Kingdom, Italy, The Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Poland, Greece, Denmark and Hungary, where nationalists and populists with different political affiliation are already in power; not to mention the case of Spain ahead of the parliamentary election of December 20, with political movements sprung at grassroots level (Podemos, Ciudadanos), from the streets, distant from traditional political parties. Although this fact does not diminish the significance of the French vote, it places it within the European scenario, unquestionably in line with populist movements enjoying consistent popular consensus.

No magic wand. There ensues that

the multifarious analyses on the Paris attacks should take into account the fact that widespread public fears – triggered by the economic crisis, migration, terrorism, external threats – have no borders;

and that traditional parties’ credibility is being questioned from Scandinavia to Sicily, from Lisbon to ex-Communist Countries; that voters are increasingly influenced by rowdy slogans typically found on the web, including the “yearning for simplification” and “magic wands”, namely, ready-made formulas to address the major problems of our times. Indeed, the situation requires in-depth reflections coupled by articulate and complex answers resulting from efficient policies inspired by ethical principles, strengthened identities, markedly prone to dialogue, for the purpose of concrete, far-sighted governmental action.