Jubilee

Pope Francis puts his foot on the threshold of the hearts of those he addresses, as when we want to prevent a door from slamming for a sudden blow of air. Those who “have been shown mercy”, writes the Holy Father, must in turn become “vessels of mercy”

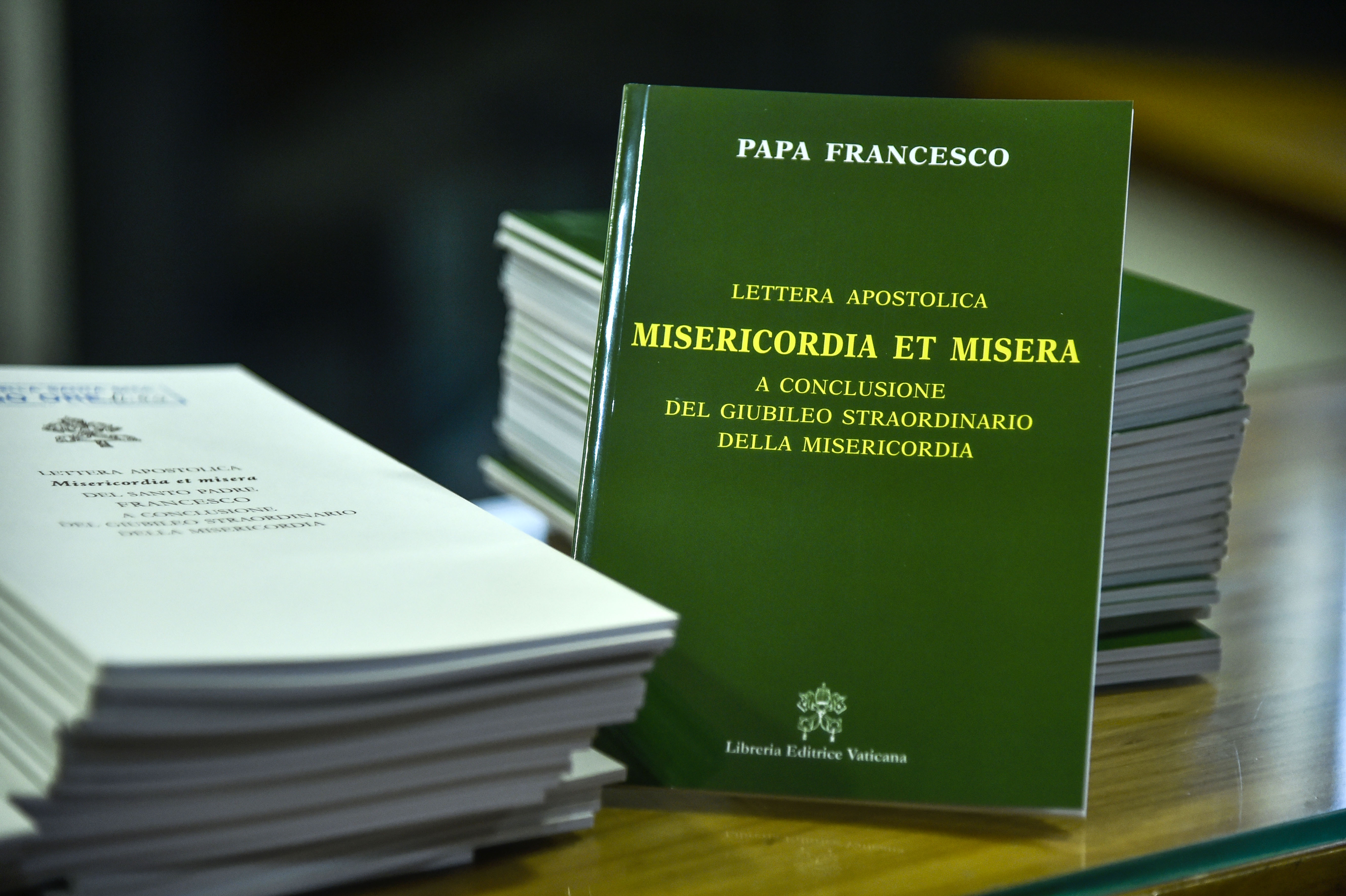

Biblical rootedness, liturgical contextualization, theological argument and, above all, experiential concreteness: these are the registers that resonate harmonically throughout the Apostolic Letter “Misericordia et Misera” that Pope Francis has given to the Church on the day marking the closing of the Extraordinary Jubilee celebrated worldwide. It would be enough to comment on the title to demonstrate the symphonic rendering interlacing all these registers: drawn from St. Augustine’s comments to the Gospel passage describing the adulteress forgiven by Jesus (Cf. Jn 8: 1-11), this title extends down to us the echo of the good news, filtering it through the patristic tradition while conferring to what for St. Augustine was the misery/mercy polarity, a personal, inter-relational profile, hence less abstract, capable of evoking the figure of the poor woman who was received and saved by the Merciful Master.

Misery and Mercy are considered within their mutual interweaving.

In fact they are already united at etymological level, since the first, misery, is totally incorporated in the second, in mercy. Their etymology ratifies and expresses a more radical involvement, which results in an existential attitude: as St. Augustine wrote in his Sermon 358A, a veritable short treatise on mercy, the latter is to be understood as when “someone else’s misery touches and pierces your heart.”

The bishop of Hippo wrote:

“Mercy gets its Latin name ‘Misericordia’ from the sorrow of someone who is miserable. It is made up of two words: ‘miser’, miserable, and ‘cor’, heart. So when someone else’s misery touches and pierces your heart it’s called ‘misericordia’, or soreness of heart.”

Among the synonyms of ‘misericordia’ used by St. Augustine in the text, figures the term commiseratio, feeling soreness of heart for the miserable, or to be miserable with the miserable, to become miserable with other miserable ones, sharing their state of extreme poverty (the true meaning of “misery”), “the lack of what is fundamentally necessary to live, resulting therefore in spiritual despondency, unhappiness and sense of desolation” (from the Treccani dictionary). In contrast to the epigones of Stoicism, St. Augustine called mercy an essential characteristic of God and a human virtue that draws humanity closer to God. While even in the fourth century AD some philosophers deemed mercy a passion that does not suit to the wise, hence almost a vice that exposes decisions to emotional conditioning or removes lucidity to knowledge and serenity to discernment, for St. Augustine – instead – mercy opens the horizons of another wisdom, a wisdom-Other, which refers to God and allows to know Him in the depths of His authentic identity, not as an impassive obnoxious, who in his misunderstood metaphysical perfection mistrusts all forms of pathos and maintains an aseptic countenance of apathy, but as someone who is capable of compassionate sympathy, a redeeming sympatheia, of a divine disposition to com-passion and even co-suffer.

The God of mercy St. Augustine referred to is the God of the Bible, whose abundance of mercy prophet Isaiah said he wanted to always remember (miserationum Domini recordabor: Is 63.7). It is the God who in Jesus Christ shows once more his tendency to be moved, that is, to go beyond his own transcendence, as Adonai – God – declared to Moses at the burning bush (Ex 3,8), to enter the state of the humiliated, of the most miserable man (Phil 2,6ss).

The God of mercy St. Augustine referred to is the God of the Bible, whose abundance of mercy prophet Isaiah said he wanted to always remember (miserationum Domini recordabor: Is 63.7). It is the God who in Jesus Christ shows once more his tendency to be moved, that is, to go beyond his own transcendence, as Adonai – God – declared to Moses at the burning bush (Ex 3,8), to enter the state of the humiliated, of the most miserable man (Phil 2,6ss).

In this respect mercy is far more than an emotional predisposition or attitude. Rather, it is a theological feature that is “Christian” in nature.

This does not mean that only Christians are able to appreciate the reasons for mercy (St. Augustine quoted Cicero as an ancient advocate of mercy), or that only Christians are capable of being merciful. It means that

Mercy tells us of God

and, more precisely, (although all major religious clearly refer to the merciful God), the God of Jesus Christ, the God that enters the realm of what is opposite to Him while never ceasing to be God, the Lord, thus exposing himself to death while being the Living (Phil 2:6-8), entering the state of sinner while being the Holy of Holies, having become a curse for us while knowing no sin, deserving all praise and blessings (Gal 3:13). He took on himself the “service of exchange” diakonía tes katallagés, as Saint Paul writes in 2 Cor 5:18-19: the young Rabbi of Nazareth had proclaimed it in the Parables, as the one on the Samaritan and the one on the prodigal son.

In the Apostolic Letter it is stated that the concreteness of the life of Jesus, misericordiae vultus, should have an effect on the lives of Christian believers who have received the grace of the Jubilee, so that – although the Holy Door in Rome and those in other churches around the world have been closed – the folds of the heart of each and every one may remain open. Hence the Pope himself places his foot on the threshold of the hearts of those to whom he writes, as one does when trying to prevent a door from closing abruptly owing to a sudden gust of wind

Those who have been “shown mercy”, writes the Holy Father, must in turn become

“vessels of mercy”

Francis’ placing of his foot represents, for example, the faculty granted from now on to all priests to absolve the “grave sin” of abortion, or, furthermore, the establishment of the World Day of the Poor, to be celebrated on the Thirty-Third Sunday of Ordinary Time. The “social character of mercy” must be preserved, thereby paving the way to “the culture of Mercy”, the Pope says. Hence mercy must be part and parcel of our daily lives, stripping the disciples of Jesus from “inertia” and “indifference”, and replacing those elements with “participation” and “sharing.” This should become a convinced and determined vision of the world, that is not “theorized about”, but rather by progressing in history extensively become a real and true civilization of mercy.